PRIZE WINNING BOOKS 2024

SHORT STORY UNPUBLISHED

TOWNSEND WALKER

Black Crescent

The bride wore a satin gown with an open draped back. Estelle saw the birthmark on the bride’s left shoulder. She saw it, as the bride passed her, walking up the aisle, Estelle saw it close. Unmistakable. Against bridal white. Her hand shot to her mouth to cover her gasp. Rose. Rose, the baby she gave up twenty-seven years earlier, had the same black crescent birthmark.

* * *

Estelle met Rose a week earlier at a small supper given by the bride’s godmother, Charlene. Estelle thought the bride handsome, a face of angles, lightened by steel-blue eyes, framed by long tawny hair. She spoke in a drawl leavened by education in the north. Rose made Estelle talk about herself. Not something she normally did with strangers. Estelle confessed to spending all her time and most of her money on books. She was reading It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis, about the possibility of fascism in America, and recently finished Colonel Lawrence by Liddell Hart, a solid man, a life rudely told. Rose had read those books. And the two found, to their delight, their judgments on the subjects in harmony. They moved their chairs closer and leaned into one another. Parting, they took one another’s hand and kissed. A rare young woman, Estelle thought. This supper with her best friend and goddaughter came off as Charlene hoped. She had intuited like-mindedness and empathy.

Charlene, a war widow, had come to Columbia from Louisville in the mid 1920’s to become Adair County High School principal. Louisville is where Charlene became Rose’s godmother. Some years later Rose’s father, now a widower, moved to became pastor at Columbia Presbyterian.

* * *

The church was decorated as Estelle had never seen it. Arches of pink roses the length of the aisle with a pink satin carpet for the wedding party. Intertwined candles and roses formed wings on each side of the altar.

But Estelle could not stay for the service. She could not stay and not say anything. She could not remain silent when the minister, Rose’s father, asked “Does anyone know of any reason why Rose Anne Stringer and . . .” She surely would walk up to the altar and say, “This girl is my daughter. That man, there, is the true father of the bride.”

That man, there, in the first pew, on the right side of the aisle, was father of the groom. He was the father of the bride and the groom. George. He had acquired the veneer of money since she hadknown him. A florid face, a tight shave, a shiny dome, and 20 extra pounds. But she knew his low-set ears and the tilt of his head.

Georgehad been born in this town. From a broken home, he had run the streets, but learned to dress, to talk, to look good, even when doing bad. Muscle for Jesse Jacobs. Jesse would make you a loan, find you a car, provide you pleasant company, anywhere in Adair County.

Estelle slipped out of church so as not to disturb the ceremony, so the others would not miss her, not Reverend Springer, not Charlene.

She persuaded the limo driver to take her into town. The temperature had climbed into the 90s. “The ceremony will last another 30 minutes. You will have time,” she said, and gave him a dime tip.

She sat in the back seat of the car, a Packard, 1935 model, with an oval side window. I told myself back then, I’ll never see her again, if I do, the birthmark is how I will know her, know my baby. She looked back at the church, studied it, and turned away, before the chauffeur drove off.

* * *

Estelle gave up her baby with considerable reluctance. Her affair with the baby’s father had been a long one, and despite George’s reputation he had been a generous and considerate suitor. She’d even had hopes. But when she became pregnant, he refused to support the baby or her. He tossed her $20 and left town. He would not get stuck in a two-bit burg with a wife and kid.

She had been a salesclerk at Woolworth’s cosmetics counter. She had no choice about the baby. She could not support it and had no family to lean on. She was not told the name of the adopting couple. Better she did not know, the agency said.No fuzzy boundaries that way.For months after, she walked to the park after work. With no one around, she leaned into the ancient oak by the pond, and wept. Later, she went to night school, and landed a steady job as bookkeeper for Champion Construction, a regional builder.

* * *

Estelle read the wedding announcement in the newspaper. It said the groom and his family were from New Orleans. So that’s where George went. The groom graduated from Tulane and worked for an investment bank in New York. The groom’s father was a senior vice president at Whitney Bank. The groom’s mother was on the board of the New Orleans Museum of Art. The paper said Rose graduated from Yale Law, nowworked in the District Attorney’s office in Manhattan.My baby did well, she thought. And she is smart. I do not know if I could have done so well by her. But Charlene’s supper was more than I’d ever hoped for. To see her, a young, thoughtful educated lady, with a prestigious job. To touch her, to kiss her. My baby.

* * *

Estelle didn’t sleep. For two days and two nights her brain burned. Finally, she called George. “Are you going to tell them?”

“I am not, you have no proof. You’re making this up,” he said.

She said she had pictures and a birth certificate and the birth mark.

“I did not sign any certificate.”

“Parents don’t, George.”

“And if you say anything Estelle, you will regret it, I swear.”

Estelle froze in fear. She did not know what to do. She went to the library and read everything about the health problems of children whose parents are genetically linked. She wanted to talk to Charlene, but her friend was out of town. Then the new school year started, and Charlene was busy day long.

A month went by, Charlene told Estelle that Rose had a miscarriage. The couple had gotten a head start. The embryo had a severe heart defect. Rose and her husband sank into despair. Rose came to town to be with her father, for consolation and healing.

* * *

Estelle called George, father of Rose, father of Rose’s husband, pillar of New Orleans society. “Now will you tell them?”

“Your crazy story,” he said.

“Think of your child, your children. Think of your grandchildren.”

George shouted, “Have that stain on my family. We are not white trash!”

“Then I will. They must know,” she said.

“Do not do that.” George banged the phone down on his desk.

Estelle would talk to Rose and her adoptive father, Henry, on Sunday, after the service, in two days. She was determined. She would do this.

* * *

Charlene did not see Estelle in church on Sunday andwent to her apartment. A knock and no answer. She turned the knob, the door opened. She found Estelle’s body tossed across her bed like a rag doll. Bruises on her arms, around her throat. The next day, the newspaper carried the story on its front page.

Rose was shaken when she read the news. The woman with whom, even if for such a short time, she had felt such a bond, she would never see again, never talk with again.

Charlene asked Rose a favor, “Would you go down to the police, they could use someone with big city experience, I’m sure.”

“I’m not really sure what I could do,” Rose said.

“For me, honey.”

The next morning, Rose walked into the police station on the square in downtown Columbia. At the entrance, a policeman sat behind a desk, a screen for visitors. Behind him, a large room with desks and men. On the walls, a U.S. flagand the Kentucky state flag. “May I talk to the detective in charge of investigating the Davis murder?”

“That’s Matt Schmidt, over there.”

Schmidt, a large man, square jawed, wide bright eyes, she felt saw everything clearly. She admitted she probably could not be of much help. She did not know the territory but worked in the District Attorney’s office in Manhattan and had been part of some criminal investigations. The victim, Estelle Davis, was a friend of her father and godmother.

He reached out and cradled her outstretched hand in his palms, “This one is a real mystery to us, ma’am, any help would be useful.”

* * *

The door to Estelle’s apartment was not forced. It had not been locked. Estelle knew the killer.They walked into a living room wallpapered with scenes of the English countryside and with four tall overflowing bookcases. As her eyes swept the book titles, Rose felt a pang. She knew theywould have talked for days. In the bedroom, Van Gogh prints of children, Baby Marcelle Roulin. The killer wasn’t searching for anything. Nothing was out of place. They found a few pictures in the desk drawer. One old photo of a woman holding an infant. Probably a baby girl, a bow in her hair, puckered lips, hand around her mother’s neck. The mother looked maybe eighteen, nineteen. Rose took the photo with her.

That night, at Charlene’s home, Rose asked if Estelle ever said anything about a baby? “No, never. Adair County Hospital is just outside town, on Route 17. They’ll have records.”

Estelle Davis had a baby, 27 years earlier. The baby’s name was Rose Marie. The father of the baby was George Bridges. Who was George Bridges? They found him in town and school records: son of Mildred (nee Adams) and Fred, parents deceased, graduated from Adair County High, 49 years old now.

* * *

Rose called her husband. “Sugar, some bad news. No, not about me. I’m fine, ready to come home. I’ve been missing you terribly. But something happened. Remember the woman I told you about, the one I had such a lovely talk with at the supper the week before the wedding, before you came. She was killed. No, no one can figure why.”

Rose explained that Daddy and Charlene asked her to help with the investigation. “It turns out she had a baby, named Rose, like me. The father’s name was George Bridges.”

“I’m sure this is only a coincidence. George is Dad’s name and I don’t know what his real last name was.” Tom said when his father came to New Orleans years earlier, he changed his name to fit in. He claimed we were descended from the Arcadian settlers.

“Didn’t you ever ask him?”

“That’s not something you did. You did not ask Dad anything about his past. Far as he was concerned his life started when he arrived in New Orleans.”

“You can’t be serious?”

“I still got stripes on my bottom from the time he saw me going into the Courthouse.”

“Sugar, Bridges in not such a stretch from Dupont.”

“Rose, I’m worried we have a problem here. You don’t think, do you?”

“Not for a second, but we should clear this up while I’m here,” she said.

“Honey, you’re the lawyer. If anyone can figure this out it’s you. But be quick, please baby, I’m not going to sleep ‘til we make sure.

* * *

Rose told Matt they needed to search the apartment again. Matt reached back in the closet, top shelf, corner, elbow-length gloves, lace handkerchiefs, diplomas, Estelle and Rose Marie’s birth certificates, apartment lease. And more photos, another of Estelle with a baby. Baby wearing diapers only. Baby with its back to the camera.

Photo lab at the police station. Blew up the photo. Cleaned it up. Rose was standing between Matt and the lab technician when she collapsed. The baby had a black crescent on its left shoulder. They lifted Rose onto a table and covered her with a blanket. Fire department arrived, oxygen. She regained consciousness. She pulled her sweater off her left shoulder.

Matt protectively bundled Rose into his car and took her back to the rectory. She went straight to her room. “Look after this lady, Reverend.”

Rose looked at the photo again, thought about the so brief, so brief time she had spent with her mother. Rose emptied out.

The next morning. “Daddy, you haven’t told me everything?”

Her father blushed; he took her hand. “You were only a month old. We should have told you. We never knew who your birth mother was, or birth father.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Mama didn’t want to, made me promise not to, a real thing with her. She wanted to feel 1000% you were hers. She told herself all the time she had spent in labor, and losing so many, there were four before she finally decided to adopt. You were her baby.”

Reverend Stringer also confessed that they changed her birth date to her adoption date and changed her middle name from Marie to her adoptive mother’s, Anne. Rose sat down, put her face on the table and sobbed. Her father rubbed her back. She swatted his hand away.

Next morning. Rose walked to the park. At the pond, sat against a heavy tree. Nothing about me is true. She wept, talked loud, talked low, through lunch, through dinner, into the hour when the swans tucked their necks into their feathers. She whispered Rose Marie. She shouted Rose Marie. Jumped up, strode back to the rectory.

“I am going to find the son-of-a-bitch who killed my mother. And, George Bridges.”

Two days later, Rose walked into the police station. Matt jumped out of his chair to help her in. “You’re alright? Should you be here?”

“Thank you, Matt, but I’m not fine china. Let’s go find the killer.”

“No known enemies in town,” Matt said, “Out of town, who knew her?”

“What about her phone calls?” Rose said, wondering why Matt hadn’t checked this before.

At the phone company they found that Estelle had made a call, two days after the wedding, to Whitney Bank in New Orleans. Then, three calls in the last two weeks. Two to the same number. She’d received one from that number.

“Strange. My father-in-law, George Dupont, is a senior vice president there.”

“Say again.”

Rose explained.

“Let’s go see him,” Matt said.

“Not right away,” Rose said.

Rose had Matt call the Louisiana Vital Records Department for Orleans Parish. Two days later the news came back that twenty-seven years earlier George Robert Bridges petitioned to change his name to George Robert Dupont.

“Now we can go see him,” Rose said.

* * *

Rose called her husband. Told him he needed to hear this sitting down. She explained about her birth certificate and about their father’s name change certificate the police found in New Orleans. “Sugar, I am so sorry,” she said.

He did not understand why.

“It’s about children. We cannot have them, not our own, yours and mine. Can we live with that?”

Her husband balked. Brought up all the inconvenience of condoms. The sloppiness of pull out and pray. “Can we talk about it some more, when you get home?”

“Sugar, there is nothing to talk about,” Rose said. “After what happened with our first one. If we want children, we adopt.”

“I don’t know.” Her husband hesitated, “There won’t be more Duponts.”

“Do you not understand? There never were.”

“What would Dad say?”

“That matters? This is about us. Not him. I’ll call when I get back from New Orleans. In the meantime, I want you to think about this.”

“Say hi to Dad.”

* * *

“Mr. Dupont, I believe you know that your daughter-in-law is also your daughter?”

The banker blustered and hollered. “Some made-up story from a crazy woman over in that two-bit burg she and my boy got married in.”

Rose patiently explained that George Bridges is the name on her birth certificate and the New Orleans courthouse has a record of a George Bridges, born in that two-bit burg, becoming George Dupont some twenty-seven years earlier.

“And why?” Matt asked, “Did you buy a train ticket from New Orleans to that two-bit burg the day Estelle Davis was murdered, and back the following day?”

Mr. Dupont said he had business in that town. Dinner with a customer.

“You arrived at seven in the evening, left at seven the next morning. Ten hours round trip for a dinner?” Matt said.

Rose and Matt led George down a path that put him in the town, with no customer, “We checked Whitney’s records before coming down here, sir.” And the police had fingerprints from Estelle Davis’s apartment, full prints, probably a man’s, from the size. Not matched yet. And then there were the phone calls. “What were they about, Mr. Dupont?”

“Goddamnit, that woman was about to ruin my family’s name. The time, the effort, the money I put into getting here, a senior vice-president of the biggest bank in town, New Orleans society. I couldn’t allow it!”

* * *

Rose called her husband. “Sugar, things are not well down here.”

“What happened?”

“Our father was arrested for first degree murder.”

“Why?”

“He strangled my mother.”

“Are you sure?”

“I am sure because I was there when he confessed.”

“Rose, before you go, I keep thinking about this baby thing, I just don’t know.”

“I’m sorry you don’t get it, but what’s to get?”

A week later, Rose’s husband met her at Penn Station in Manhattan. Porters followed her with five wooden crates.

“What are those?”

“My mother’s books.”

“Where are we going to put them? Where are we going to sleep?”

She blew him a kiss as she led the porters to a waiting truck. “I know where one of us is. Seems we’ll be having more than a few things to talk about, won’t we, Sugar.”

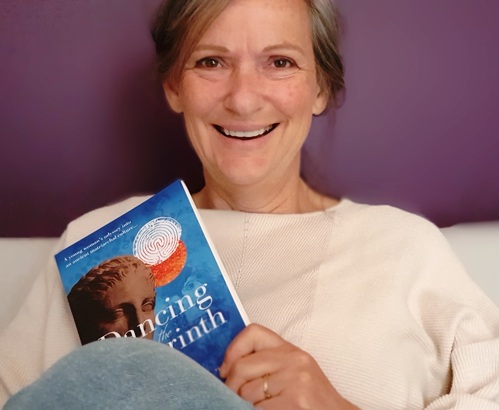

SELFPUBLISHED BOOKS

KAREN MARTIN

Dancing the labyrinth

CHAPTER ONE

Cressida hugged her book. She had studied the Australian classic My Brother Jack by George Johnston last year in her literature class at college. Ithad beentransformational – nothing less than her passport to a new life – for it had revealed a precious secret: you could choose to go and live on a Greek island. It was an epiphany, she decided. She sat smug with the knowledge that she was escaping her drab neighbourhood of monotone houses with rigid doors that remained closed against the sunshine. The grid of conformity had finally lost its hold.

She re-checked her safety belt. The reassuring band held her tight against her window seat. She replaced her book with an in-flight magazine. Idyllic beach scenes lazed across the page. Crete was renowned for its turquoise seas and white sands. And pink, she grinned,the thought offering a maverick sense of joy.She fumbled in her pocket and retrieved a small container. She slipped a pill into her mouth and swallowed. One could never be too sure.

Crete had been an easy choice. Get away, the sirens had sung, and lured by an array of aiding and abetting cheap flights, her usual struggle in making decisions went on hiatus. It made sense to runaway to the birthplace of the Gods; as a child, she devoured Greek mythology, never fairy tales. She had read everything about the goddesses of old: Artemis, Athena, Hera, Demeter and Persephone. Time had been her co-conspirator as she immersed in their fantastical tales – eons away from her desolate reality.

Sitting compliant in her seat, she counted the minutes to take-off. Countdown to forever. Forever would take a bit over four hours to reach from England, and as she gazed up, distracted by its possibilities, a crack opened just wide enough to let an image of her mother slip in.

What the fuck?

Mother had no forever, not now. Cressida shifted in her seat. The man next to her had taken up all the armrest. She examined her mother’s image cautiously. Mother who, despite years of physical beat ups and emotional teardowns, never left the man she loved. Cressida turned the page of the magazine. She coughed and rubbed her nose.

As the plane began to taxi, she pushed her head firmly against the headrest. It wouldn’t be long now. Her hands lay clasped in her lap, her elbows in tight – a lifelong lesson of constraint. Body memory shuddered as he swaggered in, uninvited, trespassing her mind. She tried to block him but it was too late.She could at least avoid his face by focusing on the damage to his car. Side-swiped by a young learner driver. The car was a write off. Both cars were. The young driver had survived. Cressida felt glad about that. One less victim.

Her mother had stayed with her father in the hospital, sitting bedside for the two days of his coma and then mourned at his graveside, before succumbing to the eternal embrace of grief. Cressida had thought, had hoped, she was free of them.

*

The island airport greeted her with nonchalant hospitality and casual security checks. The bus into town maintained an aura of effortless welcome. Sipping her coffee, Cressida marvelled at the Venetian port. She never knew such beauty existed. She bought an English-Greek language book and set about organising a few day trips to learn more about the paradise she had inadvertently chosen. It seemed impossible that she was breathing in mythological air and walking down ancient paths.

Delight coloured her discovery of an older civilisation than the familiar pantheon of Greek gods. These Minoans worshipped a Snake Goddess. This Goddess was not any Adam and Eve fly-by-night snake, but a full-on Earth Mother, Divinity Goddess of Everything. The Minoans had been the most advanced European civilisation in the Bronze Age around 2000 BCE, and the island bore testament to many ruins of their cities, temples, and palaces.It was unbelievable to think this history had not been in the curriculum.

‘Perhaps it was taught on a day I wasn’t at school,’ Cressida thought, instinctively touching the slither of a barely visible scar on her forehead.

*

Brilliant sunlight streaming through the open window of her small flat in the picturesque village on the south coast woke her. Waking was never easy. Had she slept, or been hit? Possibly worse, was she waking from a panic attack? Immediate signs were noted: her pants were dry, there was no blood in her mouth or taste of vomit. She blinked rapidly to help recover memory and take in her surroundings. It took a moment to register where she was, and then her smile matched the sun’s. She had done it. She had a new home, a new job, a new life. She still couldn’t believe that she had been living here for several weeks. She had found the perfect village, where you could either walk in on trails or take the ferry. There were no cars, only pedestrian traffic.It was a destination, not a thoroughfare.

She had not dared to hope.She had learnt that for such a small word, it weighed heavy with expectations. Hope came with no instructions, only tears. She had come to Crete looking for escape; hope held no place in her dreams. Escape had been achieved.

Opening the door, Cressida welcomed the day. The crisp morning air kissed her skin. She struggled down the sandbank, her pink feet still tender against the particles of rock and stone,and was rewarded with a quick swim to the buoy and back, in pristine water.

*

It was a short stroll to the taverna where she worked; one of many, lining the shoreline with umbrellas and beach beds. The steady pace of service and laid-back attitude of her island’s hosts made work a pleasure.By late afternoon, the horn from the departing ferry was her prompt to collect the empty glasses, plastic frappe cups and overspilling ashtrays.

Cleaning up was already agreeably routine, and her thoughts wandered freely into stories, myths, or songs. She was accountable to no one,mindless work allowing for traversing trails of daydreams. Such was the power of the island that she could not help but be inspired. Tables cleared; she retrieved the mop from the back cupboard behind the bar.

“Where is my Greek broom?” she joked with the manager, searching out the hose. What he called the ‘elastic’ did a fine job, and she took pride in the glistening marble floor. Once done, all was ready for the next shift of patrons who would arrive any time after 10 pm for dinner and drinking.

It was when the day’s work was done, the current book read, and time was her own that Cressida struggled. Settling in was more difficult than she anticipated. She was not hungry, but her stomach complained. It felt empty, like something was gnawing away, creating a hole, a gap – some sort of nothingness.Keeping busy meant walking, swimming, drinking. And drinking. And drinking. She revelled late into the midnight hours with her new friends, Tequila and Margarita, and danced with Dionysus in uninhibited glory.

Waking up became more difficult for different reasons. Her head hurt. Over the weeks, strong Greek coffee became a morning ritual. It was a relief when the nothingness in her stomach began to feel full. She blamed the fluttering on the copious amounts of raki shots and beer she consumed. It was, however, persistent.

Unbelievable. You idiot.

She lifted her head from the toilet bowl, before having even peed on the stick. Her self-criticism was familiar.

Bet it will be blue – just my luck – blue for positive, blue for a boy. Fuck.

Mother would have called her tardy.

More ‘negligent’, I reckon.

“Kalimera. Umm…”

Her Greek had not progressed very far.

“Umm, I want ah, na thelo oh, you speak English? Great.”

She booked into the city hospital for a thorough check up, slightly more invasive than the urine strip.

*

Anxiety hitched a ride to the hospital. Her clammy palms reminded her to take deep breaths. The ferry was on time, gliding effortlessly into port over an oil-slick sea. Choosing a seat upstairs in the morning sun, Cressida adjusted her sunglasses before turning the page of her book. There was irony in considering terminating the residue of a random night of passion while immersed in a paperback romance. The ferry snaked its way past sheer rock cliffs standing sentry.

*

With the cold jellied tip of the ultrasound pressed to her tanned belly, she stared at a blob outlined on the screen. In the background, she heard the nurse proudly exclaim that she may be right, perhaps it was a boy, although admittedly it was too early to tell. Contempt seethed. A boy – not bad enough she was pregnant – but a boy?

“I don’t want a boy. Actually, I don’t want a baby, but especially not a boy.”

The nurse discretely left the room, avoiding the dark tone of Cressida’s outburst. Cressida poked her belly.

‘Whoa, now what would he say about this?’ she asked. She had not thought about her father for such a long time. She swallowed and tried to laugh it off. It sounded hollow and empty.

“Hey, you there, do you think…”

Tears started to fall.She ignored them.

“Do you think…”sniff, “you can come…”another sniff, “…come into my world.”She swallowed.“And… and… just change everything? Demand everything… just cos, just cos you’re a boy. Like your dick makes a difference? Do you?”

Memories as a daughter contaminated any possible maternal instinct. Accusations scratched at her throat.

“Are you gonna be a…?” she whispered hoarsely. “A fucker like him? Are you?Comes with the territory, you know. It’s in your DNA. Oh, he would like that.”

Tears prickled their downward path. The thin thread of emotion binding her to her father was a baited hook and leaked pain. Jagged breath splintered her lungs.Faded bruises and unseen scars rose to the surface of her skin. She sweated loathing.

What would he have said about this? The ache in her heart dilutedher wrath. Incessant thoughts and questions started to crowd out her thinking and she could not find any clear space to sort it out. She bundled up her belongings and fled the women’s clinic with its scent of responsibility.

Outside, a glint of light flickered, catching her attention. “What the…?”

She looked up. The sky was blue. It was an enormous wide blue sky. The brilliance of light shone through its blueness. It was so absolute and certain. She had never noticed before. The blueness of the sky held everything, and yet nothing, in all its vastness. It stretched into infinity. She breathed in the pause.Breathe out, breathe in. Relax.

OK.

The lapse was short-lived. An incoming tidal wave of released emotion crashed through her mind, tumbling thoughts in its wake: Fuckfuckfuck. What have I done, what should I do, how could this happen, why, what should I do, what can I do, it’s not fair.

His words rode her tears as she dribbled angst into the world.

“You were right Daddy, I am dirty, I’m nothing, I deserve this. It’s my fault, it’s all my fault. I’m a dirty, dirty slut. You said so. You were right. I am so sorry, so sorry. Daddy?”

Disgust reached down into all her dark hidden places. She cramped in response and moaned. It ripped through her gut as disdain flexed its muscle. Wiping her streaked face, Cressida sneered at her pitiful state; no backbone, no grace. Woeful.

Numbness crept up, offering respite, but Cressida shook it away. She deserved to feel this bad, to be punished. It felt like home. Her thoughts scrambled through a maze of dead ends. She could not find any answers, consolation, or resolution. Her head spun. She stood up.

“Get out!” she pleaded aloud. “Enough. Enough now.”

Determination entered her game plan and speaking into the world outside her mind helped regain some control. Revulsion retreated and her thoughts receded to background clamour. This, Cressida could work with. She resigned to being pregnant for a few days longer, until she could clear her head of the white noise that had turned red.

Feeling like she had somewhat corralled the unrelenting chaos, Cressida boarded a bus to return to the port. She sat down the back where it was empty of passengers. When the bus stopped again, at some indistinct part of the main road, a large woman in a colourful scarf climbed aboard with her equally large and colourful bags and packages and array of children of varying sizes. She carried a baby strapped across her very ample bosom and a small,skinny child clung tightly to her one free hand. The woman was followed by a young boy holding the hand of a smaller version of himself.They trudged down to the back of the bus and sat opposite and next to Cressida, filling all the spaces and places of her desired solitude.

The woman heaved her large form onto the seat with a grateful sigh and the assorted children appropriated the remaining space around her as if neatly arranging a life-sized jigsaw puzzle. Well, not quite neatly. There were overflowing bags, bra straps flopping down dimpled arms, shoelaces flapping and was that, oh yes, thick yellow snot riding the inhale and exhale of the toddler’s breath through one nostril. Cressida shifted in her seat to minimise any hint of body language that might be confused as an invitation for interaction. Her attempt to blend into her seat failed dismally. Her blond cropped hair did nothing to help.

“Hello dear, yassas.” The woman addressed her in accented English. Cressida smiled weakly; there was no escape except point-blank rudeness. Before she could answer, her attention diverted to the young boy. She watched as he pulled a tissue from his pocket and wiped the toddler’s nose. Just like that. Everything in that moment seemed to change. Cressida felt a wave of gratitude. Nope, that was nausea. The woman turned and thanked the boy, “Efharisto, kalo agóri mou.”

She returned her gaze to Cressida. “This one is like his father, sees the smallest things and makes good,” she explained, and ruffled his hair with a hand that miraculously seemed to be free of child, bags strap and burdens of retail. She laughed easily. “We raise our sons to be good people, yes? That is our job. Well, at least we try.”

The bus lurched and the family scene shifted abruptly with the jolt. Cressida now saw a fat perspiring woman burdened with a sleeping baby at her breast, with a hardening trail of vomit and milk dribbled on to her dress. A child clung to her hand with a plastic nappy smelling oh so unpleasant in the afternoon heat. The two boys were squabbling over some minute plastic gadget banned in any self-respecting first-world country, which, having dropped onto the floor, was rolling down to the front of the bus, sending both these brats chasing forward in howls of protest. It was a sweaty, smelly, loud, dirty example of domesticity, and, overcome with this stench of humanity, Cressida gagged.

“Stop the bus!” she blurted, “err … stasi, na stamatisei”

Standing on shaky legs, she pulled the cord to make good her escape. Fortunately, it was a short walk to the port and relief rode on a fresh afternoon sea breeze. The ferry waited patiently at the dock for her to board. It was thankfully an uneventful return trip, save for a buffeting wind and a bigger swell than usual. After disembarking, Cressida walked along the shoreline of black sand. Waves tumbled awry, splashing her calves, then sucked at her ankles as they returned to the depths.

She sat on the warm sand and watched as the waves took it in turn to crash onto the shore. She wished the day would sort itself out.

*

Cressida woke disorientated, suspended in the faint smudge of a dream. She wriggled her fingers; pins and needles prickling her hands. Had she screamed? She looked around. The beach was strangely deserted. Stiffly she rolled over and sat up. She looked out to the ocean. The waves seemed bigger than usual.

She could not remember falling asleep, but she could remember the dream. The sole gift of a recurring dream is in knowing the outcome. She shook her head hoping to shake out the dregs, but the images remained. Caught between wakefulness and sleep, she could still see a younger black-haired version of herself rowing a small boat. The craft was laden with woven baskets filled with animals. A previous dream stocktake had revealed a rooster, several hens, a urine-soaked billy goat, two does accompanied by knowledge one was pregnant, two sheep and a ram. They weighed the boat down. Although the ocean was calm, Cressida knew a storm would come.

She also knew that the boat would land safely in a small harbour. Yet her fear remained in the creases of time, for when the storm broke, with the rising crescendo of waves and rain lashing her face, it was impossible to see the cove from the water. Moreover, the young dark-haired Cressida was only a child and she had to carry the heavy responsibility of keeping the entire livestock safe, a weight just as solid as the massive oars held in her weakened arms. Cressida would wake screaming and drenched, soaked from either the waves of her dream or the sweat of her fear.

The mayhem in her mind realised she was awake and raised its volume. Her thoughts lobbed back into overdrive. Dozing off had only provided a temporary reprieve. Swallow, focus, deep breaths, plan of action – her doctor’s instructions echoed. Meditation might help, medication definitely would.

She looked for her pills – were they in her bag? She had not needed them since arriving in Crete. Was that four, maybe five weeks ago? Time here seemed to move at a different pace. Time was different; everything was different. If only she had not ruined it.

POETRY PUBLISHED

& WRITERS CHOICE AWARDI have decided to remain vertical – Gayelene Carbis

Australia

Marrying Freud: Ladder to the Moon

After ‘Ladder to the Moon,’ a painting by Georgia O’Keefe

I.M. Ania Walwicz

I dreamt I married Freud.

He was turning down the bed when I turned to see him,

one hand held midair as if he were conducting

something, an alertness on his face at a faint strain

of music, or a sound outside.

I thought of strutting past him in my new sleekness, all those

kilos I’d lost without him, while he was away and I was

alone. I’m so small after all, and those seventy kilos

had surrounded me, like I was keeping the world away.

Then he went away and now they’ve gone. So here I am,

standing at the door watching him as he prepares

in that painstaking way he has, slow but steady, and I thought –

I’m really not sure about this.

I’d leapt into love and sex (not in that order, he’d say)

when I was young and green, I didn’t know what I wanted –

a man, a house, a baby, a life. I knew I needed to write,

nothing else could have me.

I would never see a man now, I don’t know how other women

do it. Justifying male therapists with father issues and transference.

Power is always between you, like the sheets,

like sex, as he’d say. When Freud patted the sheet

as if it was his dog, I was galvanised into

action. I went back to the kitchen, sat at the table and wrote

about my day. It took me all night. He hates

sleeping alone. I stayed in the kitchen and when he came out,

bleary-eyed in the morning, I let him make his own coffee,

I’m not his fucking mother. When I woke from the dream, I decided –

there are going to be a few changes around

here.

###

Haunted

I’d filled the house with furniture.

Then thought, I’d better tell the landlord

I’ve moved in. The house was huge;

there were empty spaces out the back,

a rambling yard. I was in Buckley St.

~

When the Egyptian left, he’d said,

Buckley St! What hope did we have?

Still I dream of my beautiful house

that was never mine.

~

I stand behind the terylene curtain

and look out the window. I watch

the neighbours. Next door, there are hippies,

former housemates of mine.

They wanted to keep bees and chickens

in the courtyard, near the compost.

A few doors down, a woman I knew

in primary school who’s returned to the area

I’ve never left; her face has grown hard.

People show up in your dreams to show you

something but how can you ever work out

what? My Lacanian analysis is cryptic.

~

You will live and die in Carnegie,

the last thing the Egyptian said as he left,

standing at the door, then turning towards me

from the front gate. He made it sound like some

sort of crime. Though, he was prone to

statements like that, matter-of-fact,

almost factual, as if foreseeing the future is

possible. He believed in destiny, your life

mapped out and, ultimately, chosen by God.

He knew I thought it was the life I’d chosen.

But had I? Had he? Circumstances, family

and society bearing down on us.

I threw the yellow roses he’d bought me

that Christmas Eve, my birthday, in the bin.

I asked him if he knew why and he did.

In the dream, I tear the terylene curtain.

Call out to the neighbours, hide behind

the torn curtain. I know they will all find out soon

that I’ve moved back in

without asking anyone

if I could.

###

The Memory of Colour

After your painting ‘Angophora, Salamander Bay 2001’ by David Rose

I.M. Judith Rodriguez

I have decided to remain vertical.

Though there are footprints all over

my eyelids, my body,

I haul myself out of bed and

into bathers, knowing

how a day begins can keep you

upright just a little bit longer.

These morning routines,

like cats, wait on the window sill.

I am no longer a woman who wears

a hat and rides her bike around

Carnegie but now and then I return to

my bike like a long-lost friend.

I slip out of my sandals and leave them

on concrete while I walk in

bare feet all the way to the place

where I lock the bike.

The walk back is about twenty steps

and sometimes that is all it takes

to remember green, to feel it

in your feet. To feel practically feline.

I hover on the first step then wade right in.

I hold the colour of the sky

in my arms, and swim.

NOVELS PUBLISHED

ISTANBUL CROSSING

by

Timothy Jay Smith /France

DAY 1

Ahdaf dropped a coin in the tip bowl and left the hammam. The hectic street quickly robbed him of the languidness he had enjoyed stretched out on a hot marble slab. He dodged pushcarts and deliverymen, some shirtless in the warming day, and jumped out of the way every time a boy, clinging to the back of a wagon piled high with boxes, shouted warnings as he hurtled down the hill with nothing more to brake him than his heels in thin sandals.

It was no less chaotic inside Leyla’s Café. People—mostly dark men like himself with some amount of facial hair—sat around small tables, their voices competing to be heard, arms flailing the air as they acted out the stories they were telling. A tobacco cloud hung overhead, abetted by the men puffing on shishas that sent up drifts of sweet, tangy smoke.

Ahdaf squeezed between tables and dodged outstretched legs to reach the cowboy bar, a short counter in a cubbyhole so nicknamed because, on the walls around it, Leyla had tacked pictures of Hollywood’s most celebrated cowboys and nailed a line of cowboy hats to its overhead arch. Its three stools were predictably empty. Beer was acceptable to be drunk at the tables, but for most customers, sitting at a bar drinking beer or anything else suggested they embraced elements of Western culture, a direct affront to popular fundamentalist notions. That didn’t stop them, however, from recharging their phones with the power strips that Leyla had laid out on it. Only one socket was available and Ahdaf claimed it before someone else did. His charge was in the red zone, down to a suicidal three percent given when his own life depended on his battery’s life.

Leyla stubbed out a cigarette and flipped her black hair off her shoulder. “Are you coming from the hammam?”

“How can you tell?”

“You smell like soap.”

“Is that good?”

“It’s better than you smelled yesterday.”

“Was it bad?”

“You’re not wearing your usual blue shirt either.”

“I washed it. This is my back-up while it’s drying.”

A stranger, pushing up to the bar, said, “Sounds like you could use a third shirt.” Out of the corner of his eye, Ahdaf saw that he was older but not by much, and he could’ve passed for Turkish but his accent said he wasn’t.

“I only have two hangers,” Ahdaf replied, not looking at the man, not wanting to engage with anyone who wasn’t a potential client, and the man was too well-dressed to be a refugee.

“Do you want a mint tea?” Leyla asked him.

“Tea?” She knew Ahdaf would want a beer. Then it dawned on him, maybe there was something amiss about the stranger and that was her signal. “Yeah, and with an extra sugar,” he said. “My body weight tells me I’m undernourished.”

“That’s an extra lira.”

“Okay, no extra sugar. I don’t want you getting rich off me.”

Leyla laughed. “Get rich off you? I couldn’t get rich off all you guys in here put together, no matter what I was selling!” She dropped a third sugar cube into his glass. “On the house.”

He frowned as he stirred his tea. “We had jobs in Syria. I could’ve made you rich then.”

The stranger offered his hand. “I’m Selim Wilson. Sam if you prefer.”

Ahdaf ignored his hand. “Why would I prefer Sam?”

“It’s what I was called growing up.”

“You changed it to Selim?”

“My mother’s Turkish. Selim is on my birth certificate.”

“While you guys decide on his name, I’ve got other customers,” Leyla said.

“Before you go, do you have cold beer?” Selim asked.

She looked at Ahdaf when she replied, “Only one is cold.”

“I only want one.”

“It’s mine,” Ahdaf spoke up.

“You’re drinking tea.”

He took a sip and pushed the cup aside. “I pre-ordered the beer. Very cold.”

“I tell you what, you guys share it.” Leyla uncapped the bottle and planted it between them, along with two glasses, before squeezing around the end of the stubby bar to serve tables.

“It’s all yours if you want it,” Selim said.

“We can share it,” Ahdaf replied.

“Then I insist that it’s my treat.” Selim angled the glasses as he poured to produce only thin heads of foam. He passed one to Ahdaf.

“Thanks,” he said and took a sip. “Are you American?”

“Is my accent that obvious?”

“It’s an accent. I like to know where people are from.”

“It’s American,” Selim confirmed.

“If you’re an American, you must know who some of these guys are,” Ahdaf remarked, referring to the cowboy pictures Leyla had tacked to the walls.

“I know a lot of them. Not personally, of course, but from the movies.”

“Maybe you should take a selfie in a cowboy hat and stick it on the wall,” Ahdaf suggested.

Selim snorted. “It takes more than being an American wearing a cowboy hat to meet Leyla’s standards. I think you also need to be a movie star.”

“I think she just likes cowboys,” Ahdaf replied. Now that they were talking, he couldn’t help but notice how handsome Selim was, his dark beard groomed and his eyes chestnut brown. “I don’t think all those came from movie stars,” he added, pointing to the cowboy hats nailed overhead. “Have you been to Leyla’s before?”

Selim nodded. “Yeah, occasionally.”

“I’ve never seen you in here and it’s basically my office.”

“Obviously we work different hours.”

“I’ve also never seen another American in here.”

“I’m Turkish American. Maybe that explains it. Or maybe the fact that I wanted to meet you.”

Ahdaf’s danger alarm went off. He’d met lots of strangers at Leyla’s. Refugees were his clients and her café was where they knew to find smugglers to help them make the crossing to Greece. Selim, he sensed, wasn’t looking for that kind of help. “Why do you want to meet me?” he asked.

“I’ve heard you get things done.”

“What things?”

“Moving people.”

“Who told you that?”

“A lot of people could have told me.”

“But who did? I like to know how people find me.”

“He. She. It. I don’t remember.”

“Why the secrecy?”

“I need a reliable route for people to escape.”

“Escape what?”

“Turkey.”

“So you’re a smuggler, too?”

“Not like you, or why would I need you?”

“You don’t need me. Lots of guys do what I do.” Ahdaf checked his phone. “It’s charged enough,” he reported and dropped it into his daypack.“Are you CIA?”

“I can’t say who I work for. Not until we have an agreement.”

“Then I guess I’ll never know. Thanks for the beer.” He slipped off the barstool.

“Just remember, Ahdaf Jalil—”

“How do you know my name?” Ahdaf interrupted him.

“Just remember,” Selim started again, “what you call ‘moving people’ is trafficking to the rest of the world. Turkey could deport you back to Syria. Back to Raqqa and ISIS. Back to a push off a high rooftop.”

“Why have you come looking for me?”

“I told you, I want your help.”

“I don’t want to help you.” Ahdaf stood to leave.

“Take this.” Selim forced a business card on him.

“I don’t want it.”

“Sometime you might need help. Not everyone is a nice guy like you.”

Ahdaf glanced at the card. No name. Only a telephone number with a local prefix. “Do I ask for Sam or Selim?”

“You don’t ask for anyone. You leave your name and a message, and where to find you if you need help.”

“I won’t need help,” Ahdaf said, but stuck the card in his pocket anyway. “Thanks for the beer.”

“Maybe next time I can treat you to a meal.”

“I’m never that hungry.”

Ahdaf made his way to the door of the lively café. He knew some eyes trailed him. Nobody’s business was entirely private since most of it was conducted on the street. Everybody kept an eye on each other and not always to be helpful. Selim hadn’t said he was CIA, but he was somebody like that, and probably somebody in the café knew exactly who he was.

The door hadn’t closed behind him before his phone started ringing.

DAY 2

Ahdaf found a spot on a bench to claim one of the spigots on the long ablutions wall. “Salaam aleikum,” he said to the men beside him and slipped off his sandals. Turning on the faucet, he let the cool water run through his toes as the call to prayer droned through overhead loudspeakers. Like Ahdaf, most men along the bench kept their cleansing ritual confined to their feet and forearms, but some went through the full procedure of rinsing out their mouth, cleaning their ears, and snorting water out their nose.

He dried his feet with a handkerchief and crossed barefoot to the mosque’s entrance where heleft his sandals on a shelf. Slipping behind a heavy velvet curtain, he entered the vast prayer hall with its many tiers of stained-glass windows rising to the dome. Except for worshippers kneeling on the expansive red carpet, it was bare; there was no furniture or architectural feature to break the eye’s sweeping gaze. The praying men appeared inconsequential in the presence of Allah, which Ahdaf supposed was the architect’s intent.

Ahdaf wasn’t a believer though he liked the notion of religion. He liked the superstitions and rituals that were largely for luck, health, or good fortune. The downside was that he believed very little of Islam’s tenets, especially after they had been used to justify his cousin’s execution, which made it ironic that now Ahdaf used religion as part of his survival strategy. The mosque was a source of rumors and news, and he relied on both to stay informed.

That morning there was no imam. No sermon. The few dozen men who’d come to pray knelt in loose lines, bobbing out of synch to touch their foreheads to the ground while mumbling holy words. Ahdaf joined one of the lines, not exactly to pray to Allah but to plead with his parents to manage to survive the civil war and beg his cousin’s forgiveness if he had somehow contributed to his death. Those were his only prayers most mornings, but that day, he also thought about the family he put on the bus to Assos the night before, and prayed for them to be safe, too. When finished, he sat back on his haunches, eyes closed, enjoying a meditative minute before rousing himself to discover what the day was going to bring.

Outside, Ahdaf retrieved his sandals and dropped them on the ground. As he wiggled his feet into them, someone said his name. He turned to Malik, the headmaster of the mosque’s madrasa, a scrawny man with a prophet’s beard and a dark brown kaftan the same color as his dull eyes. “Salaam aleikum,” they both said and touched their hearts.

“It is good to see you so often at prayers,” Malik remarked. “It’s apparent that you are a man of faith.”

“Sometimes a habit can be mistaken for faith,” Ahdaf replied. “My father insisted that I go to prayers once a day.”

“It is not only habit in your case.”

“What makes you so sure?”

“You still come to prayers even though your father is not here to scold you.”

“Yes, it’s true, though I wish he were. At prayers, I see many men who remind me of my father. That’s one reason I prefer to pray at the mosque, not in a shop or on the sidewalk. Also, my father always spoke of the mosque as a place of fellowship as well as faith, and I’m alone in Istanbul.”

“Does the fellowship you seek include drinking khamr?”

“Khamr?” Ahdaf asked, repeating the Arabic word for intoxicating drinks.

“Beer.”

In one word, Malik sent a seismic jolt through Ahdaf’s world. Someone had seen him at Leyla’s having a beer and for some reason that was important enough to report it to Malik. Why was it important and why Malik? As the madrasa’s director, he was certain to be a fundamentalist, but did he go so far as the hisbeh—the religious police—to spy on people? “It’s rare that I drink a beer,” Ahdaf lied, feeling the need to defend himself.

“Even one beer is still haram,” Malik said. Forbidden. “I’m surprised a man with your strong faith would succumb to the temptation.”

“Allah is forgiving,” Ahdaf reminded him.

“The most forgiving,” Malik replied, quoting verse.

“Alhamdulillah,” they both said and touched their hearts. Thanks to Allah.

Ahdaf, wanting to end their exchange, smiled and took a step away. When Malik said his name again, it felt like a summons and he turned around. “Yes?”

“What did Selim Wilson want from you?”

Ahdaf gulped. “Selim Wilson?”

“He didn’t tell you his name?”

“Yes, but how do you know it?”

“He is an American spy. What did he want?”

“He wants me to help smuggle people.”

“Who?”

“He didn’t say.”

“We want you to help him.”

Ahdaf was baffled. “Help him?”

“We want to know what he’s planning and who he wants to smuggle. If he wants information, what’s he looking for? Anything you can tell us.”

“Who are you?”

“Brothers in faith.”

Ahdaf summoned the courage to ask, “Are you part of ISIS?”

“We help everyone who fights for Allah. Will you help us?”

“I told the American that a lot of guys move people. He doesn’t need me and you don’t either. Obviously, you already have spies.”

“Apparently Selim Wilson thinks he needs you. He picked you. He didn’t buy anyone else a beer.”

“I won’t help him for the same reason I won’t help you. I left Raqqa to escape a war. I don’t want to be part of a new war here.”

“You can’t escape it. We’re in a holy war and your faith makes you part of it. The West’s only faith is greed.”

Ahdaf, feeling ambushed, shook his head when he said, “I’m just trying to survive.”

“Can you contact Selim Wilson?” Malik asked.

He couldn’t lie. Whoever had seen him sharing a beer with Selim would’ve seen the CIA man press his card on him. “Yes, I can contact him.”

“Do it.We have an operation coming up. We need to know if he knows anything about it.”

“I need to think about it.”

Ahdaf, about to turn away, stopped when Malik added, “Don’t take so long thinking about it that you accidentally fall off a building like your cousin.”

Their eye contact held for an extra moment. Ahdaf willed his eyes to be expressionless. Malik’s were confident.

Contempt was their common denominator.

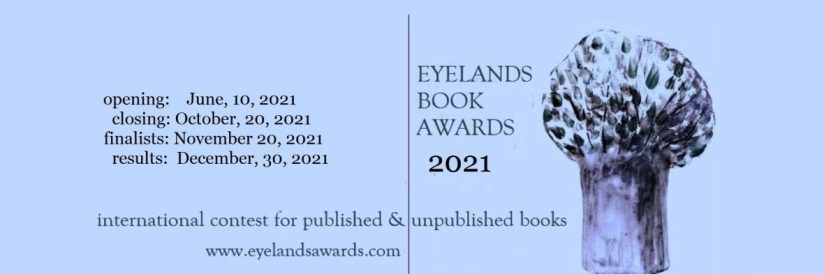

PRIZE WINNING BOOKS 2021

Τhis year, as promised we launch a new page on eyelands book awards, dedicated to the prize winning books, with excerpts of the books that won a prize in EBA 2021. With the permission of the authors we present a small excerpt between 500-700 words available to everyone! Every week, from April till 20 of June, there will be a new post at this page from our prize winning books.

You can find the text translated into Greek on http://www.eyelands.gr every Saturday!

U-18 Category: 1941 / Abigail Keoghan /Ireland

She thought of her father and the soldiers being killed, the thoughts of Conor leaving her and her family finding out she was dead; they were flooding her head. “No, no, please no, stop it” Aoife yelled “Leave me alone”. She placed both of her hands on top of her head like she had a headache. She arrived at the channel in time. She made it there, all by herself; she didn’t need anyone to finish this mission. Aoife sped into the bunker as fast as lightning. She saw a man of average height with short dark golden hair and eyes the colour of the sea. Aoife ran towards him.

“ Hello, who are you?” Aoife asked the man. The man turned his head to see Aoife.

“I am Lieutenant Mackenzie, what are you doing here?” the man asked. Aoife was stammering until she remembered what the mission was about. “I came from England with a message from GeneralKemp, the attack needs to be called off” Aoife panted.

Lieutenant Mackenzie looked at Aoife with suspicious eyes. “I don’t trust any girl who says that” Lieutenant Mackenzie replied. Mackenzie walked off and called the attack. “ No, don’t please” Aoife screamed.

The attack was launched but the Germans were prepared for this. All of a sudden, there was blood-curdling screams, gunshots and explosions. Aoife ran out there as fast as she could to see hundreds of people running and falling to the ground. She had to run, there was no turning back. She ran like she was being chased by a bear. Aoife ran as people were falling and explosions were ignited. She saw a boy in front of him fall to the ground, his leg was stuck. Aoife needed to help him. She ran up to him. The boy was tall and had black curly hair, tanned skin and gentle mocha eyes. She went onto her knees to release his foot from the hole. “Are youokay?” Aoife asked.

The boy looked to her “I’m fine” he replied breathless.

“What’s your name?” Aoife didn’t look up, she needed to help. “Aoife, you?” Aoife replied monotonously. He looked at her “Zachary” he replied with a smile on his face. She released his foot from the hole. Zachary stood up.

“May God bless you, Aoife” Zachary thanked Aoife; before running. Before Aoife ran after him, Aoife’s photo flew out of her pocket, it was flying through the wind, Aoife ran after it. She needed it. She depended on it. Suddenly, a bullet flew through the photo needed it. She depended on it. Suddenly, a bullet flew through the photo and it was obliterated.

Aoife stood still in shock. “No” Aoife whispered. Aoife needed to move but she couldn’t. All the other soldiers were running past her until one of them pushed into her causing her to land on the muddy, ash-covered grounds, causing her to become unconscious.

Aoife woke up a couple of hours later, hearing nothing. The entire landscape was foggy and white. She rose up from the white and greyground that was once green. She looked around she saw hundreds of bodies, none were alive.Aoife couldn’t believe it. Britain had lost. Aoife was on the brink of tears. Aoife had failed her mission. She lost everything, her partner, her family, her father, everything. Suddenly Aoife heard a noise coming from the fog.

“Any survivors?” a familiar voice called. It couldn’t be. it just couldn’t.

Her father.

“Any survivors?” the voice called once more. Aoife rose up ready to shout. “Dad!” Aoife cried. “Dad, I’m here!” Aoife began running with tears inher eyes to the voice, she saw somebody ahead of her. A tall man with dark brown hair multi-coloured eyes and fair skin, was just ahead of her.

“Dad, I’m over here” Aoife called once again. The man turned to herdirection. The man who once had once a frown on his face, was no more.The man had pure happiness in his eyes when he saw his daughter. They both embraced each other in their arms. “I love you, Dad” Aoife cried.Her eyes would stop releasing tears as she hugged her father. “I love you too, Aoife” her father replied.

//

My name is Abigail Keoghan and I live in Ballsbridge, Dublin, Ireland. I am twelve years old and I have a younger sister who is seven years old. I got my inspiration for writing by my book-loving aunts both wishing to publish a book. I love to write. My first book that I wrote was called 1941. It was about a young fourteen year old girl who went on a mission to save her father. I entered it into a competition when I was ten. Sadly I didn’t win but I decided to enter another competition the Eyelands book awards competition with Kenya’s Education (originally called Education or not I must learn something). I just love to write and I wish to become an author or artist when I am older.

Unpublished: The Grinning Throat (Mudlark Mystery 1) Kate Wiseman/ UK

The Mudlark Mysteries

The Grinning Throat

LONDON, 1872

CHAPTER ONE

My first thought is that it’s a pig that someone has lost to the river. Maybe that’s because food is always on mind. I’m permanently hungry and wishing for delicious, unattainable things to eat.

I think that the pig must have fallen off one of the barges that choke up the Thames. They’re a constant feature, toiling up and down day and night, giving off choking smoke that clings to the water. I’m shocked by this carelessness and I wonder that the owner didn’t try to retrieve it – pork’s expensive. A luxury. I haven’t tasted any since Dad died. Or precious little meat of any variety, if I’m honest.

The pig’s head is out of sight, hidden under the remains of a wooden crate. I’m surprised that no one’s lifted that. Wood’s got a value. Nothing to write home about – a halfpenny maybe – but beggars can’t be choosers and if we aren’t quite beggars, we’re only one step above it. The pig will still have some worth, too, if it’s not too far gone. Maybe we could clean it up and eat it some of it ourselves. The thought of meat, even meat that has been tainted by this river full of unsavoury debris, makes my mouth water.

I wonder how we missed this, the last time we were here. It must have been the excitement of making the Find.

Then it dawns on me that what I thought was some kind of cloth, wrapped around the carcass, isn’t that at all. The pig is wearing a suit, so mired by mud that I can’t even begin to guess its colour. Odd. But this is London and odd things happen all the time. Perhaps this was a lark by some gents with time on their hands and more money than sense. We see a lot of those on the foreshore.

Usually they’ve lost their precious pocket watch or wedding ring while they were three sheets to the wind and they’re trying to recover it before their wives or sweethearts find out. I’ve helped out gents like that before and they’re pretty grateful if you manage to find their lost possession, especially if you hold back from ‘discovering’ it until they’re close to desperation. There was a time when deceptions like that would have made me feel guilty, but those days have gone. You forget scruples when you’re fighting to survive.

I’m so busy calculating the value of these unexpected finds, and wondering who’s likely to give us the best price for what – Hopper for the suit, I think, although he’s a frowsty old miser who’d enjoy taking advantage of a couple of orphans if I let him, and Jack Frost for the meat, once we’ve sliced off a few of the best cuts – that it takes a while for the penny to drop. A pig? In a suit? I peer closer. My stomach does a flip. Hunger is making me stupid.

This must be what Hempson was looking for. Why he was so cagey.

‘Edie, stay back,’ I rap out the words, glancing over my shoulder. If this is what I think it is, she mustn’t see it.

Thankfully my sister is still twenty yards away, eyes roaming over the foreshore and the ramshackle hut lurking at its edge. She hasn’t noticed the thing in the mud. I think for the thousandth time that she’s really not cut out to be a mudlark. There’s no room for daydreamers on the foreshore. It’s nasty and it’s dangerous. But the alternative is even worse.

‘Have you found something exciting, Joe?’ she lifts her skirts in a pointless attempt to keep them clear of the filth and actually moves closer, eager to see what I’ve found.

‘NO!’ I swing around and glare into her eyes. ‘Stay there! I mean it!’ Surprised, she looks into my eyes. I’m never angry with her. Then she cranes around me to try and see what I’m looking at. Her mouth drops open.

‘Is that a –?’

‘I don’t know. I’ll check-‘ I try to keep the dread out of my voice. ‘Please, Edie, I need to check before you get too close.’

Every mudlark comes across dead bodies from time to time. It’s inevitable, London being what it is. But I haven’t got used to the sight, the smell, the stillness and the total absence of humanity in those I’ve discovered. I think I never will. Visions of those I’ve found, dumped as if they’re just another bit of rubbish, creep up on me when I allow my mind to relax. Nights are the worst. Sometimes I wake to blackness, heart thumping at apparitions of green flesh and eyeless faces. Please, don’t let this be another one to haunt my dreams.

So far, I’ve managed to shield Edie from such sights and I want to keep it that way. She’s too young. I know her unworldliness can’t last much longer, not in dog-eat-dog London, but as I see it, every extra day is a bonus, and I’m the only one who can prolong it. There isn’t much I wouldn’t do to protect her for just a little bit longer. That’s my job. I owe it to Dad.

Edie drops her head and stares hard at the sprinkling of shingle that’s leaving a trail across the mud. I think she has forgotten that she’s supposed to be my lookout, but that’s understandable.

I turn back to the thing on the shore, delving deep into the gritty pockets of my greatcoat for my talisman. There it is. Warm in spite of the cold day. Reassuring to the touch. I wrap my fingers around it and squeeze it and for a second it feels as if Dad is looking out for me.

I can do this.

Holding my breath, I bend down to lift away the crate.

//

Kate is a children’s writer. She lives in Saffron Walden with her husband, her son (when he’s home from university) and three neurotic cats. One of her cats, Maisie, is actually a ghost cat now, but Kate still talks to her every day.

Children’s book/Published: Sailing away to Nod/ Brenda M. Spalding/USA

Once upon a time, a young boy sailed on an ink black sea. The stars overhead twinkled and the moon showed the way. The little boat tossed and followed the wind to a far distant shore. The little boy left the boat and went to explore, as he had done so many times before. He trudged through the sand and followed the tracks that the sea turtles made. Along the way he gathered some shells, some smooth round stones, still warm from the sun and some bright pieces of sea glass all left by the waves. Beyond the sand and beyond the trees, he could see bright colored flags waving on a castle high on a hill.

He followed a path through the cool dark forest until he came to a clearing in the woods. In the clearing was a small cottage in need of repair. The roof was all sagging and the door off the hinges.

A strange little man sat in front of the door smoking a long stemmed pipe. He had an old battered hat perched on top of his head and a long white beard matched the hair on his head.

A gnome, a dwarf, the boy couldn’t tell. The man looked up as the boy approached. “Go away, there is nothing left to steal,” growled the little man.

“I’m not here to steal,” replied the boy. “I’m here to explore and see what I can see in this Land of Nod.”

“Well go explore somewhere else. I have nothing

left to steal. “

A giant lives in these woods.

“He took my cow. So I have no milk.

He took my chickens. So I have no eggs.

He took my beehives. So I have no honey to sell

at the market.

I shall probably starve.”

“I’m sorry for your troubles and wish I could

help,” said the boy.

“Well you can’t, so just go away,” shouted the

little man.

The young boy left the clearing and followed the path into the woods again. The path got steeper as he started to climb. Leaving the trees behind him, he saw a very large house with a very large door. There were chickens in the yard and a cow in a pen. He knew right away it was the giant’s house he saw. A little way off he could hear someone crying. He followed the sound and under a tree was the biggest, tallest man he had ever seen, bigger even than his Dad. The giant had long black hair and a long black beard. His clothes were all dirty and torn. His head in his hands, he was crying and moaning.

“I only wanted some honey. I meant them no harm.”

The giant looked up and shouted at the boy.

“What do you want? Just go away, please.”

“I don’t want anything,” said the boy. “I’m here to explore and see what I can see in this Land of Nod.”

Why are you crying, a big giant like you?” continued the boy.

“I’m crying because I have all these bee stings. I like honey, but the bees won’t let me have any.

They just get mad and sting me all over.” He cried even louder.

“Well maybe you should give them back to the little man down the hill. Then they won’t sting you anymore,” said the little boy.

With that the boy continued to follow the path up and toward the castle on the hill he walked. Inside the castle walls, a great fair was being held. There were acrobats and jugglers, wearing bright colors, and a man breathing fire, just like a dragon. There were stilt walkers weaving their way through the crowds. The gypsies in their tents were telling fortunes for money. They used a mystic ball and claimed to see all.

“Not one stall has any honey!” exclaimed a young girl as she stamped her foot, and started to wail.

She turned and noticed the boy and shouted. “What do you want? Just go away please, unless you have some honey to sell.”

“I don’t have any honey.” replied the boy. “I’m here to explore and see what I can see in this Land of Nod.”

“Go explore somewhere else,” the little girl stormed.

Brenda M. Spalding is a prolific award-winning author. She is often called upon to speak at book clubs, conferences, and writers’ groups. She is a past president of the National League of American Pen Women- Sarasota, Florida Branch, a member of the Sarasota Authors Connection, Sarasota Fiction Writers, Florida Authors and Publishers, and a co-founding member and current president of ABC Books Inc. Ms. Spalding formed Braden River Consulting LLC in 2020 to help other authors on their creative journey. Contacts -www.bradenriverconsulting.com

Short Stories / Unpublished: A General History of the Feminine Brain / Raluca Comanelea / USA

Hot Pockets

She put a trampoline in the living room where you constantly pass out watching all the TV shows on Earth. With utmost care, she hits pause on the remote control and throws a blanket over you, making sure that your toes are tucked in. She stares intensely. Her feminine brain exhibits a mild intoxication.

***

Your grandfather’s war medal stares you in the eye, boldly, reminding you of your long-forgotten androgens. Your chubby body remains static. You have long ago reclaimed the divan for your manly needs: pulling a nose hair with vigor, scrolling social media accounts in a premeditated order and hitting those likes mechanistically, caring less if the image depicts a fisherman or a mermaid, stirring into the food in front of you and blowing repeatedly in hopes that it cools off faster because your hunger is devilish. You barely complete 1850 steps on any given Saturday, 4000 on days you go to work, that is, if you’re lucky. Yet, you demand Hot Pockets with crispy crust. In the meantime, her culinary talents are wasted. She cannot compete with this insane need of yours for Hot Pockets.

***

You dream that your grandfather’s postwar dreams have turned reality with you. She knows they didn’t. You unconsciously wish that she expires first so that you can reclaim the whole length of the divan to yourself. You have not the slightest idea of how much she despises that divan. Her womanly heart has secretly wished for a chesterfield sofa since times immemorial: it’s been too long now to feel any fire burning.

She sits there, alongside you, numbed, waiting for you to fall asleep so that she can pause the show. She screams at the sight of the rodent. You stare emptily because in the end you know that the rodent is way too fast for any attempt at movement. Inside bugs have always given you those nightmarish creeps. Unable to catch the creature, any creature as a matter of fact, you unleash at her, exaggerating the piles of dirt which would consume the whole house. You burst into hysterical laughter because you have just laid a cruel truth out in the open. The whole thing becomes bearable now. She throws a yellow glass tumbler at you. Misses as you slightly incline your head to the left. You both know she is an awful thrower. She hates sports. Nature endowed her greatly. Sometimes you wonder why she is still there in the morning.

***

She wakes up and wonders if with today’s sun rising she is pregnant. She has learned to cultivate patience in this dry desert she permanently made her home. Her only deep-seated wish for a peaceful evening has been reduced to avoiding the crunchy sound of a crispy Hot Pocket crust coming from a mouth she long idolized, she long kept wet, she long breathed into.

Raluca Comanelea is a woman writer born in Romania. She enjoys green spaces, loose-leaf teas, and fine books. She goes to sleep with the same desire to own more time in the palm of her hand, so that her writing dreams would manifest freely. Raluca is a lover of American theatre and drama, with all sights set on Tennessee Williams and his complex female characterization. From Las Vegas, Nevada, she paints our world in fiction and nonfiction colors. Her imagined universe centers on the human drama lived behind closed doors of a dominator culture, one which pulls the average man into its vortex with an intensity hard to contain. Raluca’s novelette-in-flash, “The Art of Surviving in a Glass of Water,” has been awarded the Finalist title in the Newfound Prose Prize 2021 competition. Raluca’s creative work has been featured in STORGY Magazine, Reflex Fiction, Toho Journal and Secret Attic Journal, among other literary venues. You can connect with Raluca at www.ralucacomanelea.com

Historical fiction – Memoir /Published: Drudgeries for Feat, Identifying and Leveraging Opportunities in a Foreign Country/ Beatrice Hofmann /UK

BECOMING THE BOSS

I detected similarities where everyone saw differences and differences where everyone saw similarities. I was able to create new and unique solutions that resulted in a significant and enduring difference because I provided unique therapeutic services to people in my community around Oberhausen and its vicinity.

I have achieved so much with the support I have received from my network of friends and acquaintances. Be there for people when they need you, they will return your favour when the time comes. Partake in social functions to build your network. A key factor is to learn to network with the right people. For this, one has to understand the difference between acceptable and destructive criticism. A useful tool for this is using a SWOT analysis. It requires identifying the ‘Strength, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats’ of the people in question. Conducting such research periodically on my own business as well as family situations has also helped me to sharpen my understanding of my very own position. Migrants are always a marginalised ethnic minority in any country. For migrants to escape insecurity, adversities and harsh conditions, entrepreneurship becomes the last resort for them to survive. Many migrants have become successful entrepreneurs in America, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and several countries across the globe. However, there is a typical pattern in all these activities that ultimately define the migrant entrepreneurial activity and their journey to entrepreneurship, I will describe these patterns using my own personal experiences.

Accumulating and Using Experience

I explored, I discovered, and I assessed my surroundings carefully and drew inferences on solid grounds. During my first years in Germany, I couldn’t go anywhere smoothly because my husband and his family wouldn’t let me, even mere taking my own daughter for an evening stroll wasn’t a walk in the park. Still, after my divorce, I became geographically, physically, and mentally mobile because I wanted to learn to know and expand my knowledge. It is this accumulated knowledge that developed into well-known patterns that revealed themselves in know-how, know-who, know-where, know-what, know-when and know-why that enabled me to quickly identify and exploit opportunities almost instinctively. Knowledge breeds experience, which makes the strange more familiar as factors keep reiterating themselves in ever-increasing clarity. My experience enabled me to master the fundamentals, which allowed me to efficiently react to situations and improvise with intuition.

Opportunity Orientation

I could recognise and analyse market opportunities. With a specific combination of handling risk, content, and market, I could redefine ‘risk’ as an opportunity to use my expertise, rather than as a possible reason for failure. I found prospects looking for better ways to provide new services and new approaches as well as explored a segment of the population which I knew could respond to a recent version of services targeted to lifestyle. What helped me is that I had a well-defined sense of searching for opportunities. I was always looking ahead and was less concerned about what I achieved yesterday. Many migrant entrepreneurs have searched for or created opportunities all the time, placing themselves between a chance and shaping themselves to seize it and quickly take advantage before it gets lost. I recognised the importance of being first, fast, and right, striving to seize and take full advantage of opportunities is why I was among the first black women to enter the wellness and beauty therapy industry in Germany. Entrepreneurs must recognise that action skills that get results are more critical than perfections that result from flawless planning.

Tact and Testing the Limits

I understood how different variables impacted on each other from the knowledge I had obtained at home, work, school, relationships and the community; I continually adjusted ends, means, values, and circumstances with the awareness of each impact. All four of the above mentioned decision dimensions are variables and partial determinants of each other. It’s this fluid view of these variables that provided me with the flexibility to determine the ends, forge the means, shape circumstances, and understand their value limits. I understood the German language fluently, the German policies, procedures, and rules of the matrix system; including how and when to stretch them beyond the limits and when to strictly adhere to them. This allowed me to open up the horizon into an opportunity-filled environment that I thought provided only restrictions rather than choices. The diverse experiences that I shared in the previous chapters show how I overstretched on all fronts but didn’t punch above my weight I repeatedly tested my limits and elements of every situation, about my own God-given abilities and talent, my willingness to act, and the power and willingness of my allies and adversaries to act. This usually involves appreciating that the world has no distinct rules of fairness and that the playing field is never level. So, testing limits primarily consists of determining which way the field slants and how to slant the area in one’s favour to keep winning, and that’s precisely what I did.